|

|

|

|||||

|

|||||

A SUMMARY COMPARISON OF JUNCTION GRAMMAR

|

|

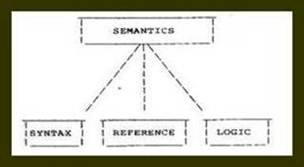

Figure 2. Syntax is considered to be an integral part of semantics in Junction Grammar.

To make a long story short, the meta-model of human intelligence of which J-rules are but a part is presumed to interact with the deep representations of JG (we refer to them as WFSSes, but you may think of them as junction markers if you like), to generate a great deal of information not explicitly represented by them. Notice that the hypothesis that deep representations stimulate more information than they contain is useful in explaining why the same sentence may "mean" different things to different people. It is interesting also to note that this hypothesis is somewhat akin to the notion of semantic interpretation proposed by certain transformationalists who oppose GS (they call themselves interpretive semanticists), but the formal mechanisms of JG for its implementation are very much different than those proposed by interpretive semantics (IS). (Jackendoff, 1972) Let us now turn to IS briefly.

The theory referred to as interpretive semantics (IS) is actually a reaction to GS, and entails a number of proposals for preserving the original position of Chomsky regarding syntax and semantics, which is, of course, that syntax can be dealt with independently of semantics. Hence, IS rejects the notion that the base rules of the grammar generate semantic representations directly. Rather, it is argued, the base rules, i.e. the P-rules, generate syntactic representations. Semantic representations are then obtained from these by processes of semantic interpretation. There are some new twists, of course. For example, surface structures as well as deep structures are now subject to semantic interpretation, and other descriptive paraphernalia have been added to accommodate "functional" and "modal" phenomena. But not withstanding these addenda, not to mention an enlarged system of P-rules, structural transformations are still required to obtain surface constituent structures. Hence, from the JG point of view, IS represents another attempt to patch up a model which is fundamentally defective. It is not surprising to me, therefore, that the adherents of GS and IS are currently stalemated amid mountains of “empirical evidence” which is used alternatively to argue both for and against both GS and IS.

It was alleged earlier that attempts to adapt standard TG to deal with semantic phenomena fall short of the mark because those adaptations "still fail to capture the range of constituent relations required to account for the meaning of sentences." The substance and motivation of this statement are rooted in certain crucial differences between the JG conception of what syntax (constituent relations) consists of and the TG conception of what syntax consists of. In order to clarify this point, it will be necessary to consider the format of J-rules and the implications of that format for semantics. A review of how that format was arrived at will also be instructive.

The decision to construct a grammar with no structure changing rules, as previously noted, established the need for a more powerful component of structure-generating base rules. Although my intuition suggested to me that constituent structures were a reflection of linguistic operations which join constituents in ways much more specific than the simple concatenation provided for by rewrite rules, it was not at first obvious what those ways were, or how to make them explicit. The first significant step towards constructing the type of rules required came when I realized that noun-phrase relative clauses, noun complements, and other modifiers were all manifestations of a linguistic operation whose output literally permeates human speech. I refer, of course to what we now term subjunction. The sequence of events immediately preceding and following the birth of subjunction in JG were also important in establishing the methodological orientation of the theory.

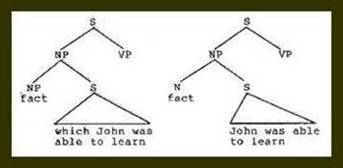

I had been contemplating for some time what struck me as serious theoretical problems associated with the phrase structure rules NP > N S and NP > N S of TG (see Figure 3).

RELATIVE CLAUSE RULE: NP --> NP S

COMPLEMENT RULE: NP --> N S

(1) The embarrassing fact that John was able to learn frustrated his adversaries.

Figure 3. The TG treatment of noun complements and relative clauses.

These rules, proposed to account for restrictive relative clauses and noun complements, respectively, both embedded an entire sentence to a nominal antecedent, encompassing both constituents with brackets labeled NP. It seemed clear that the two structures in question were in fact related, i.e. in some sense similar, but not in the way suggested by the P-rules proposed to generate them. Specifically, in each case there seemed to be an overlapping of constituents in the main clause with those in the subordinate clause: In the relative clause, an NP of the main clause coincided referentially with an NP of the dependent clause; in the complement, a noun, or noun phrase potentially, of the main clause was equated referentially with the entire dependent clause, Thus, sentence (1) is ambiguous over the relative clause and the complement readings:

(1) The embarrassing fact that John was able to learn frustrated his adversaries.

(Notice that you can replace that with which for the relative clause reading but not for the complement reading.)

There was nothing in the P-rule formulation to make this overlapping of constituents explicit, however. Hence, a mechanism for checking the coreference of NP's was required so that the relative clause transformation could apply to sentences embedded by NP > NP S and produce the appropriate relative pronoun. It was not clear whether this mechanism was supposed to establish a coreference relation between the head N and the complement S in NP > N S, however, since no T-rule depended upon such a check. Moreover, there was no

clear justification for using N rather than NP to the right of the arrow in the complement rule, since the head of a complement can have articles and modifiers too.

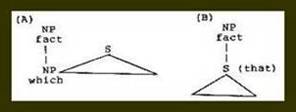

Still more serious, to my way of thinking, was what appeared to be implied by the relative clause rule. Namely, the entire clause was bracketed with a nominal category (NP), suggesting that it, like the complement, was functioning in its entirety as a nominal constituent. I concluded that the structural symmetry of these two rules resulted in a false generalization (the illusion that both clauses were nominalized) while failing to make explicit the generality which actually existed and was semantically crucial (the referential overlap between constituents in the main and dependent clauses). I therefore proceeded to devise structural representations which reflected the overlapping of constituents without violating what I sensed were the correct categorizations. This was first done in the manner shown in Figure 4 and later as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4. Initial JG diagrams for noun phrase relative clauses (A) and noun complements (B).

|

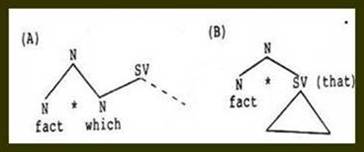

Figure 5. Later JG diagrams for relatives (A) and complements (B).

As I further contemplated the relative clause diagram of Figure 4 (A), it occurred to me that the main clause and the dependent clauses could be construed as intersecting structures. In the case of the relative clause, the intersection occurred on categorially homogeneous nodes (on NP's), whereas in the complement structure, the intersection occurred on heterogeneous nodes (NP/S) so that the entire subordinate clause intersected with an NP of the main clause. It then struck me that perhaps any subordinate clause could be analyzed in terms of its intersection with the main clause. Turning to English, and other languages familiar to me, I observed almost immediately that in addition to relative clauses which intersected the main clause on NP's, there were others which intersected on adjectives, and adverbs, as exemplified by sentences (2) and (3):

(2) Dogs such as Duke is require little food.

Clause main: Adj dogs require little food.

Clause dependent: Duke is Adj

(3) As ye sow, so shall ye reap. (You will reap like you sow.)

Clause main: Ye shall reap Adv

Clause dependent: Ye sow Adv

I likewise noticed adverbial and adjectival complements, in addition to noun complements, as exemplified by sentences (4) and (5):

(4) He walks so that his toes point outward. (manner)

(5) The set such that it has no elements is empty· (attributive)

By this time I had reformulated the original rewrite rule to be a junction rule:

NP / NP S "NP subjoin NP of S"

In order to account for clauses intersecting on adjectives and adverbs I added other appropriate rules:

(Relative) AdjP / AdjP S "AdjP subjoin AdjP of S"

(Relative) AdvP / AdvP S "AdvP subjoin AdvP of S"

(Complement) AdjP / S "AdjP subjoin S"

(Complement) AdvP / S "AdvP subjoin S"

At about this point, I made an important change in my approach to the data. Up till then, I had simply added to my list of subjunction rules as I happened to encounter structures which corresponded to them. Now, however, I began to anticipate what could plausibly be expected to happen in the way of intersecting structures. In other words, I generalized the subjunction rule to be a formula (X / Y S), and began to deduce specific possibilities in terms of the constituent categories extant in my system of diagramming at that time. Moreover, rather than rely on available data to motivate or confirm new rules, I began to use rules predicted by the subjunction formula to suggest data not otherwise available.

Why this change in my approach to data was significant becomes evident when considered in the context of rules which correspond to certain rarely used but perfectly legitimate junctions. Consider, for example, sentences (6) and (7):

(6) I fristicized my suspenders, like you did your garters.

(7) The book is on the table, which is not the same relation you observe between the picture and the wall.

Imagine how long one might search a text before finding an instance of either of these relative clause types. Each would require a special context. Yet, any grammar of English would be incomplete without the subjunction rules for (6) and (7). The fact that some rules are used less than others in no way invalidates them. In a number of cases I deduced what at first struck me as the most ridiculous rules for subjunctions, only to find that sentences formed to fit them were perfectly acceptable. It soon became apparent to me that any grammar which is based on rules arrived at inductively, i.e., simply set down in a list as available data suggests them, will be incomplete, at best, and most probably not motivated by any significant generalizations.

Not long after, of course, came the realization that it is also possible to overdo a good thing. Some of the ridiculous looking rules I deduced turned out to be as ridiculous as they looked, i.e., no language that I or my colleagues are familiar with confirmed the validity of the predicted junctions. This turned out to be a healthy period of frustration, however, since it forced the formulation of linguistic constraints on both the form and content of junction rules. The identification of these constraints in turn led to new insights into the nature of constituent structure relations and their semantic correlates.

Our research eventually produced what has turned out to be a very stable notion of what a junction, i.e., a linguistic operation which joins and inter-relates constituents, entails. Every J-rule consists of the following:

(1) Categorized constituent operands;

(2) An operation symbol which specifies the relation to be defined between the operands; and

(3) A designation of the category of the new constituent formed by the junction.

This definition of junction, plus a system of constraints designed to keep predicted junctions within the range of generalizations (similarities) and specializations (differences) evidenced by natural languages, does in fact provide a scale of semantic contrasts of the type I had originally envisioned. In fact, it has been possible to define increasingly more refined semantic distinctions, corresponding to higher orders of specificity in operand and operation symbols. A host of subtle differences of meaning can now be explicated in terms of junction alone. All of the proposed adaptations of TG still fall far short of the mark because none of them to date shows any signs of capturing even the most obvious constituent structure generalizations: To my knowledge, complements and relatives are still handled with the same old rules (the notion of structural intersection has escaped transformationalists entirely); such fundamental distinctions as subjunction, conjunction, and adjunction, are absent in their representations, not to mention the lack of any device to account for categorization patterns (see literature on JG for a discussion of these topics).

One final comment regarding the notion of structural transformation. I think it has never been satisfactorily explained from a theoretical point of view how one justifies the assumption that the transformational manipulation of structure without regard for meaning (either consciously or subconsciously) has any relevance for natural language phenomena other than, perhaps, idioms, whose structure is characteristically at odds with their semantic interpretation. Moreover, unless the realization of deep structures as lexical strings is totally unlike any other natural coding system in my experience, that process is more readily presumed to operate within constraints which make the path between levels of representation direct and straightforward rather than tortuous and obscure. Those who have attempted to devise analysis or synthesis algorithms using TG will appreciate the practical if not the theoretical implications of his point.

And that is the final broad distinction I wish to draw between JG and current versions of TG. It is, of course, a corollary of JG's basic premise - that base rules generate all constituent structure directly, while lexical rules interpret and reflect that structure, but do not alter or add to it in any way. Hence, except for idiomatic expressions or instances where morphological devices have become ambiguous or inert, JG makes the tacit assumption that surface strings are a reliable and direct reflection of the deep representations underlying them.

This concludes my discussion of broad differences between JG and TG. There are, of course broad similarities to be noted also, but a consideration of these is beyond the scope of this paper. For the present, given the general areas of divergence discussed thus far, an enumeration of some of the more salient specifics of JG is offered in Appendix A.

1. Meaning is considered to consist of:

A. Structure (junction relations and categorial contrasts)

B. Reference (the denotational value of linguistic tokens)

C. Context (connotation, inference, presupposition, etc.)

2. Trees are generated either from the bottom up or from the top down.

3. Relations between nodes are shown as junction operations. Three basic junction types are:

A. Subjunction - accounts for modifiers of all kinds,

B. Conjunction - accounts for nodes coordinated by and, or, but.

C. Adjunction - accounts for relations between subjects and predicates; also between predicators and objects.

4. Patterns of categorial predominance are expressed.

5. Junction rules are categorically schematic as well as referentially schematic, i.e. every J-rule is derived from a junction formula.

6. Lexical rules interpret rather than transform. (There are no rules in JG which bring about a structural change.)

7. A. Lexical ordering rules specify order of interpretation (trees do not express any explicit linear order for nodes)

B. Lexical hiatus rules suppress the application of lexical matching rules and never delete nodes from trees.

C. Lexical matching rules do not insert lexemes into the tree, but into a lexical string which exists independently and apart from the tree.

D. Lexical agreement rules do not copy feature information from one node to another, but cause affixes to appear in the lexical string if certain feature information appears in the tree.

8. Features are used in JG to abbreviate tree structures or to specify information furnished by the information net or the logic.

9. Junction rules can be used to diagram fragments of discourse as well as to diagram sentences.

10. Each junction relation has a semantic correlate. Even subtle junction contrasts result in semantic contrasts.

11. Junction relations are directly associated with phonological phenomena.

12. Junction rules are considered to be a universal pool of possibilities from which all languages draw.

13. Lexical rules are language specific, although certain formal properties of lexical rules are shared by all languages.

Chomsky, Noam. Syntactic Structures.The Hague: Norton & Co., 1957.

_____________. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax.Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1965.

Jakendoff, Ray S. Semantic Interpretation in Generative Grammar. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1972.

Katz, Jerald J. and Postal, Paul M.In Integrated Theory of Linguistic Descriptions.Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1967.

Lytle, Eldon G. A Grammar of Subordinate Structures in English.Hungary: Mouton & Co., 1974.

______________. Structural Derivation in Russian.Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Illinois (Champaign-Urbana), 1972.

______________. "A New Look at Grammar." Unpublished paper presented at BYU College of Humanities Seminar, 1969.

[1] Paper originally presented at the Languages and Linguistics Symposium, Brigham Young University, 1975

|

[Home] [Origins] [Article Archive] [Foundations] [Formalizations] [Analyses] [Pedadogy] [Forum] [Guest Book] [BYU] |

|

Copyright© 2004 Linguistic Technologies, Inc. |