JUNCTION GRAMMAR

IN

FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHING

by

Royden Olsen

Translation Sciences Institute

Brigham Young University

1972

In this paper, I describe an experimental application of junction theory to foreign language teaching. Specifically, an attempt was made to facilitate the teaching of Portuguese grammar and conversation to a group of missionaries at the Language Training Mission by supplementing the present program with an exposure to junction grammar. This approach incorporated the tree structure representation system, which was used to present selected points of grammar as well as a stock of the basic syntactic structures of Portuguese. I theorized that, because of the formal nature of junction grammar and because of interesting findings about the structures of Portuguese observed this year in connection with the machine translation project, the grammar of a language could be taught more explicitly and graphically by supplying visual diagrams which illustrate grammatical relationships in simple, easily understood way. Assuming this were true, it followed that language could then be explained more efficiently. This would create more time for the students to actually communicate, and, at the same time, give them a clearer working concept of the target language structures involved.

The practicality and desirability of the experiment were suggested, in part, by the demonstrated utility of junction theory in accounting for syntactic phenomena in explicit terms. Aside from its analytical powers, the theory gains a high degree of acceptability among students because of its correlation with what is felt on an intuitive level. That it does not alienate itself from human linguistic intuition may be partially due to the fact that junction theory draws from traditional grammar in many instances, such as in the area of parts of speech where major categories of words are roughly equivalent in both traditional and junction grammar. Thus, the student has an initial basis for reference.

Another consideration influencing the application of the theory to pedagogy is that the tree structures can be adapted as a visual teaching aid. In making this application, I introduced some basic simplifications in the tree diagrams in order to overcome the major cause of failure in previous language teaching experiments which incorporated transformational grammar - unwieldy complexity. Illustration 1 makes this point graphic.

In addition, the trees represent syntactically what happens in the deep structure and they separate morphology from syntax. Therefore languages can be compared on a deep syntactic level and the morphological peculiarities of a given language can be analyzed with reference to the underlying structure. The trees can be manipulated to reflect the lexical ordering of a specific language as well. Hence, the trees become a powerful tool for contrastive study. Because of this contrastive quality, it is hoped that the common problem of interference from native language patterns will be lessened, or at least elucidated. Also, since the production of sentences is a creative, or generative, process, whatever insights a student may gain about the linguistic mold into which he fits his utterances will be helpful in this creative process.

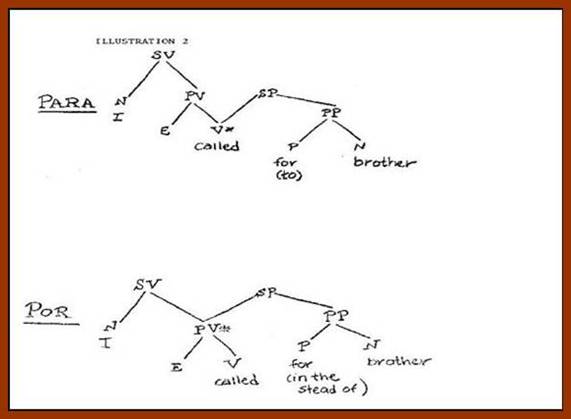

Finally, I wished to incorporate the results of some of my studies in Portuguese. Research on the translation project has shown that what we do intuitively in language is much more structured than is generally imagined. For example, a well-known area in teaching Portuguese, as well as Spanish, is the case of por and para, two prepositions in Portuguese which quite often map into the single lexeme for in English. An example of this is the sentence I called for my brother. Two of the possible meanings of this sentence are 1) I wanted him to come, or 2) I called in my brother's stead. In Portuguese the first of these meanings translates with para and shows directionality from the verb. (See Illustration 2.) The second meaning translates with porin a prepositional phrase of adverbial force which modifies the whole predicate (PV).

What on the surface seems like a complicated problem turns out under analysis to be a basic structural difference. Furthermore, some cases of ser versus estar, the two to be verbs in Portuguese, can be handled easily because of basic underlying structural differences. Also, such notions as noun clauses are graphically explained with tree diagrams.

I believe that using a scientific approach to learning something as complex as language is a valid approach and, as will be seen, certain questions of grammar can be resolved in an ultimately more satisfying way to the student because of the inherent clarity of the system.

In this experiment, the aim was first, to teach enough of the theory for the students to understand some of the above examples as well as other examples which will be described and second, to note any increase in the students' ability to handle these forms in a speaking situation. I also wished to counteract the typical dialogue memorization and parroting with a working knowledge of some of the basic structures of Portuguese. To do this I designed language drills around the tree structures to promote a more creative learning experience and to raise the level of language competence.

In the following section of the paper I will outline the classroom procedures of the experiment. All mention of text, lessons, and lesson numbers refer to the current Language Training Mission textbook, PortugūesparaMissionįrios, 1971 edition. The experimental group consisted of six students. An additional group of six was taught concurrently using the standard Language Training Mission audio-lingual approach.

On the first day of class, the basic principles of junction theory were presented using English examples. The basic operations - adjunction, subjunction, and conjunction - were explained and illustrated, and all of the elements of the trees which would be utilized throughout the three week course were presented. Basic drills were utilized.

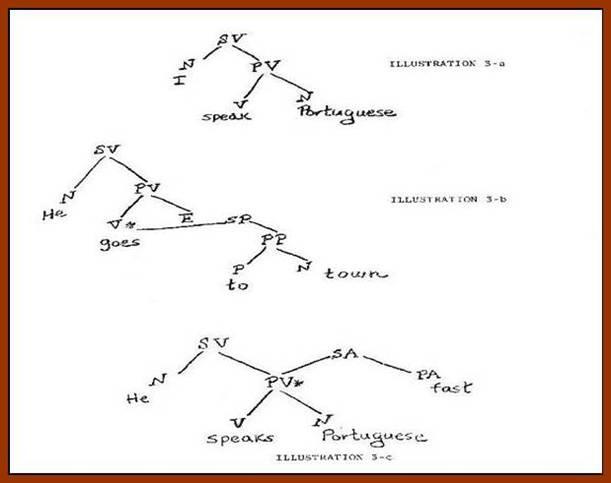

The first structure presented for use in conjunction with Portuguese drills was a simple sentence (SV) with no subjunctions. (See Illustration 3-a.) At this point subject-verb agreement drills were introduced, comprising roughly lessons one, two, and three in the Language Training Mission text. To further accommodate the agreement, substitution, and question-answer drills of these lessons, the following structures were introduced: Illustrations 3-b and 3-c.

When the above sentence types were presented, the tree diagram was drawn on the board, grammatical implications were discussed, and examples were given when needed. Following this, a Portuguese version of the tree was supplied and the standard repetition, substitution, and question-answer drills were practiced. This was the pattern used in all ensuing lessons.

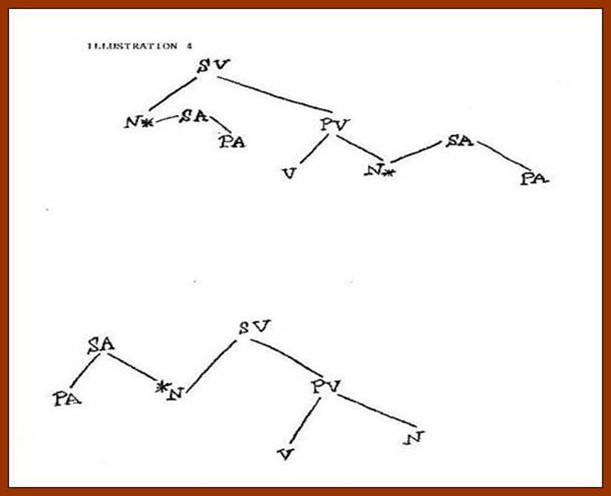

Lesson five introduced adjectival modifiers. The appropriate tree variations were used and generalizations were made about placements of modifiers in Portuguese. (See Illustration 4.)

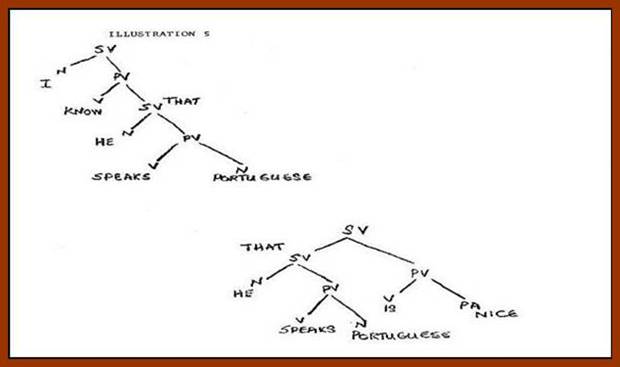

In lesson six, the structures in Illustration 5 were introduced. Knowledge of both structures was to be vital in lessons seventeen, eighteen, and nineteen, which deal with the subjunctive in the imbedded SV (noun clause). This structure also proved useful in illustrating sequence of tenses.

The bulk of the grammar in the remaining lessons concerns tense, mood, and aspect in the Portuguese verb system. However, special cases in which the use of junction grammar proved fruitful were:

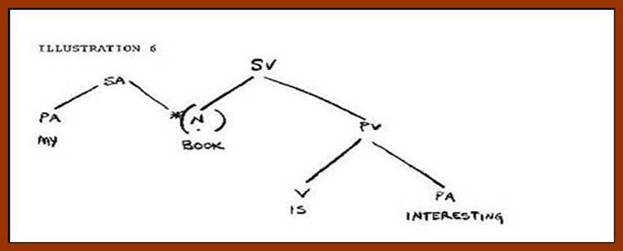

1) Lesson 11 - Possessives

In this lesson, a series of charts and complicated explanations are usually used in an attempt to differentiate between possessive adjectives and possessive pronouns. We presented one tree showing that the lexicalization of the N node in parentheses was optional, and then practiced one comprehensive drill which included both options. (See Illustration 6.)

2) Lessons 17, 18, and 19 - Subjunctive in the Noun Clause

In my experience, this was the first time students were able to visualize from the outset exactly what a noun clause was.

The first of these lessons was presented by a teacher other than myself who had been learning the trees along with the students. Here are his comments:

The main value of the use of the sentence tree in teaching the subjunctive was the clarity and the logical sequence that followed the brief explanation.

I just drew the tree that is used for the embedded sentence and had them write some sentences to fit the basic patterns using verbs like saber and dizer. I then showed them how the subjunctive is formed. After these two steps had been completed, and with the basic tree still on the board, I was able to show them how a change in subject is made, where or how to recognize a noun clause, and, easiest of all, the position of the verbs that require the subjunctive. It was very smooth and I think that the few hours spent to explain the tree and do the drills will save many hours of explanation in the future.(Tom Johnson)

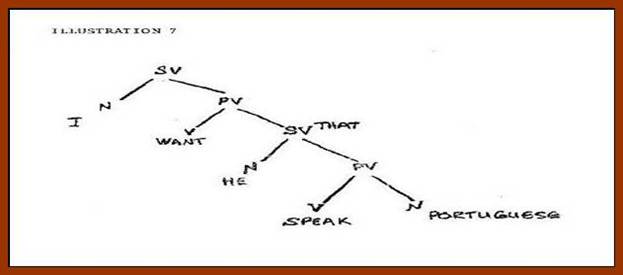

Variations of the tree in Illustration 7 showing other possible imbedded SV's also proved useful for explaining the concepts of adjective and adverbial clauses, and sequence of tenses.

3) Grammar books list approximately twelve different instances of the prepositions por and para in Portuguese. Most of these cases can be elucidated in terms of Illustration 2. The students' familiarity with these two trees made their understanding of the fundamental differences between these two prepositions simpler and more systematic.

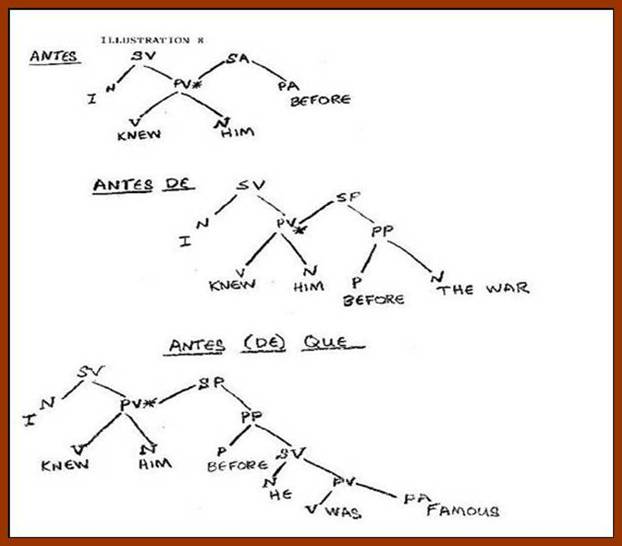

4) A common problem for non-native speakers of Portuguese is the confusion of the categories of words following the pattern of the series antes (adverb), antes de (preposition), and antes (de) que (conjunction). (They all translate with the word before in English.) The trees in Illustration 8 provided a graphic differentiation among the three forms as well as a logical progression to the concept of subjunctive mood in the adverbial clause.

It was also noted that in complex structures, component parts of the structure could be drilled using the visual representation to keep the part being drilled in context with the whole structure.

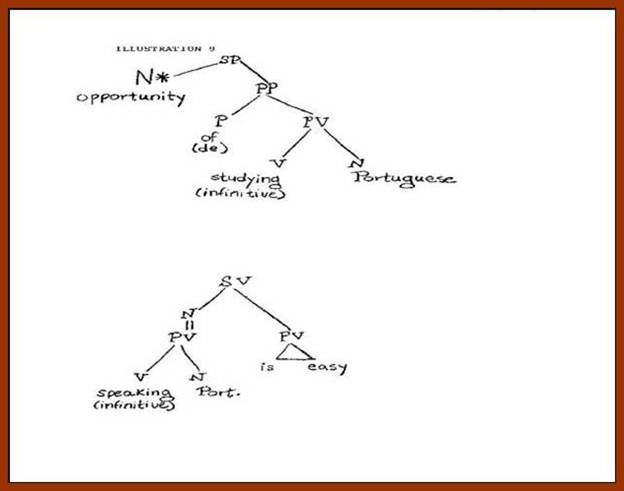

5) Because of the students' ability to interpret the trees, a certain economy was achieved in teaching Portuguese structures on the order of de plus an infinitive to modify nouns, or the use of the infinitive in Portuguese corresponding to the English gerund. (See Illustration 9.)

During the three week course, tests and continual review were conducted. The review consisted of conversation, question-answer routines, tree diagrams for which students supplied Portuguese examples, sentences to be diagrammed, and creativity drills. The creativity drills were composed of lists of nouns, adjectives, verbs, etc., from which students were instructed to form their own sentences based on their knowledge of basic Portuguese structures. Tests were of two types:

1) standard weekly grammar tests, and

2) creativity tests, a written version of the creativity drill.

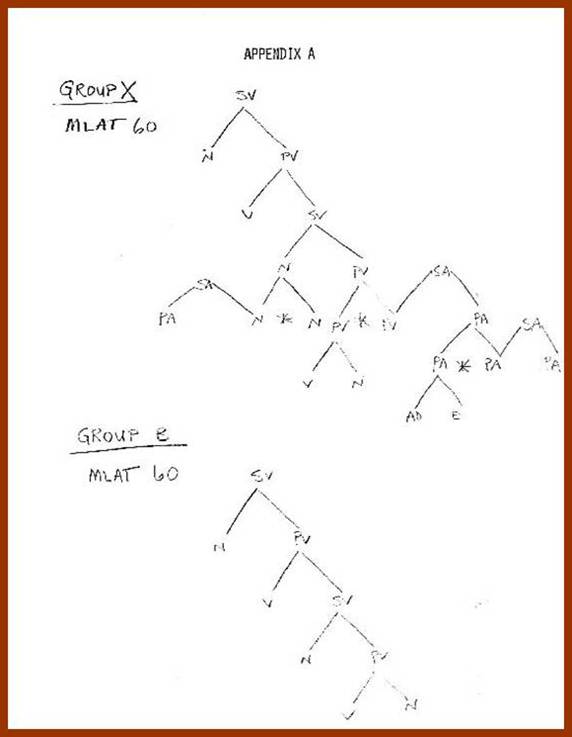

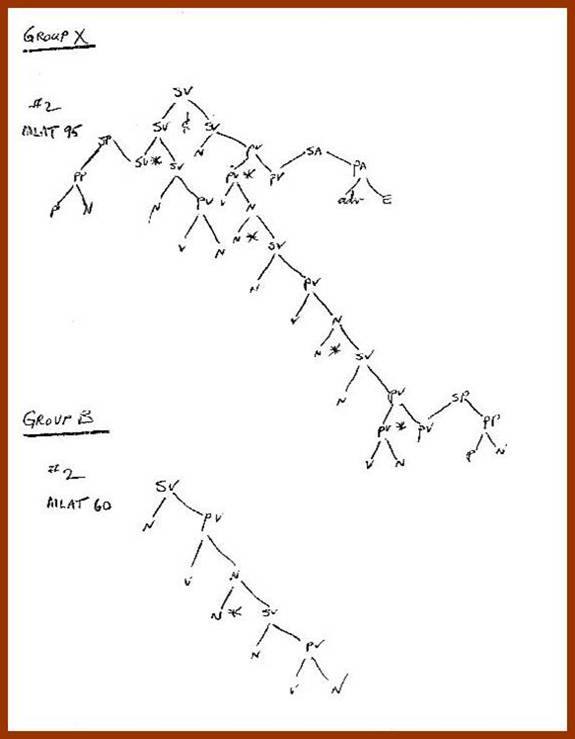

The tests were administered concurrently to the group using junction grammar and to another group which was at the same level of study. The average Modern Language Aptitude Test, or MLAT, score of the experimental group (group X) was 63, while that of the other group (group B) was 55. To facilitate a direct comparison, six students were scored in each group. (The six students from group X included one with an MLAT of 95; without him, the group X average would have been 57.)

To date, creativity test results have shown some positive tendencies in favor of the experimental group, namely, 1) the use of more complex structures; 2) fewer idiomatically non-acceptable structures; 3) fewer categorial errors (using adverbs where adjectives should go, using a past participle instead of a verb in the past tense, and so on); 4) a better grasp of the grammar; and 5) fuller utilization of the vocabulary.

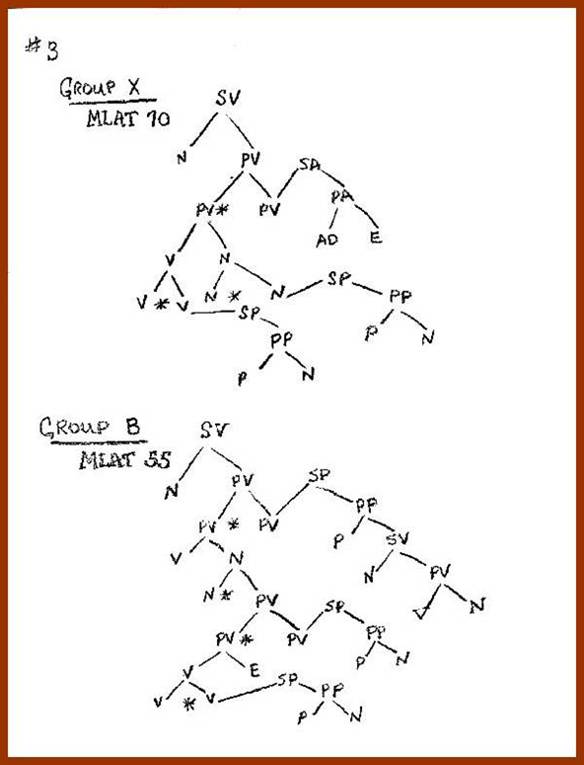

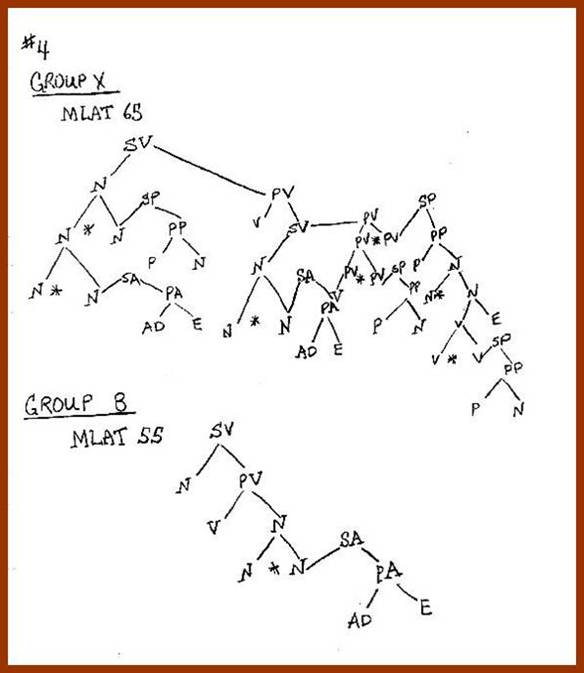

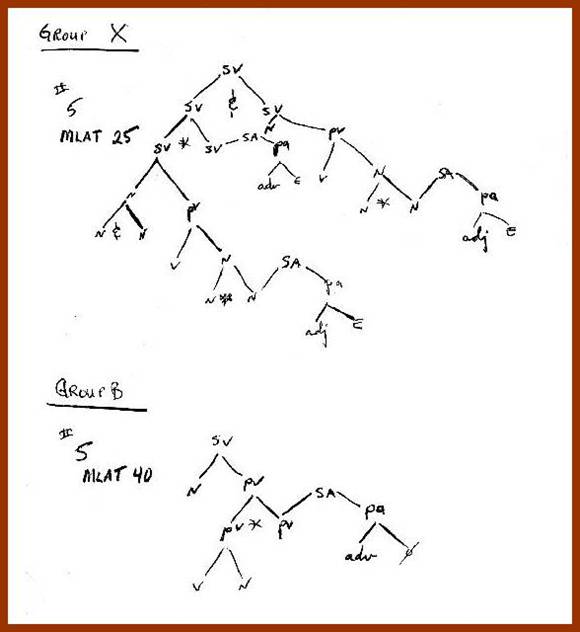

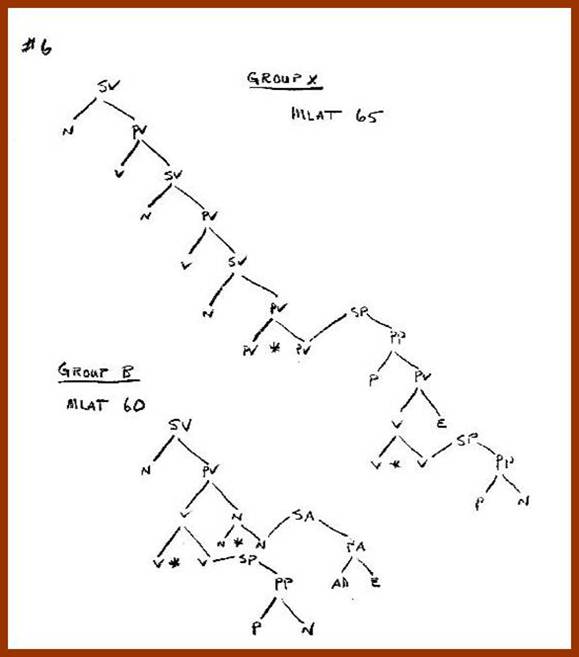

Appendix A has sample structures taken from a creativity test administered to the two groups after their second week of study. For the comparisons we chose the most complex, structurally acceptable sentence from each student's test and then paired these sentences. In each contrastive pair, MLAT scores are included.

On the six tests of group X, there was only one unacceptable structure (made by the student with the 95 MLAT) compared with seven in group B (which also included six tests). Agreement errors were sixteen in group X and twenty-seven in group B. Also, the ratio of grammatical errors on the weekly unit tests was about three to five, with group X making fewer mistakes.

The students themselves were asked to give their reactions to the trees:

The trees seem to me to be an excellent way of teaching and learning sentence structure. They are not so complex, like the sentence diagrams I had to learn in grammar school, that they confuse rather than elucidate, yet they do fulfill their intended functions. I have studied other foreign languages, but I have never been able to pick up sentence structure so quickly. If you could find such a simple way to teach other things - like how to remember vocabulary - you could shorten the time in the mission home again.

The trees are okay, I guess. They are a lot like diagramming sentences in English. They do help a little in clearing things up now - and I'm sure that later on when things get more complicated they'll help a lot more. They're kind of fun, too.

I have previously studied French and German in high school and college, but have never before acquired such a good understanding of the structure and function of a language so quickly. The "trees" and creativity drills give me a basis for conversing realistically. I feel they've provided me with the necessary tools to assimilate my ideas and express myself in Portuguese rather than merely repeat verbatim lines of static dialogues. The audio-lingual method used in my other language studies didn't facilitate learning to converse in realistic situations. I'd recommend that this structural approach be incorporated into the Language Training Mission program. I think it will better equip the missionaries for the challenge of handling their mission languages in the field.

I studied the sentence structure trees in high school in English, but I never really understood it until now. I think knowing how this works helps me in my sentence structure. Especially in learning a new language where the sentence structure is different. It's like learning English. You must know where everything goes to form a good sentence.

It is my opinion that the visual presentation of grammatical structure used is not only advantageous in learning and comprehension, but I feel it is superior to equivalent visual methods now in use in English grammar training,

(Signed)

P.S. I like it, too!

This tree system seems to give roots to language learning. It enables you to incorporate past experience with language structure, etc. with the task of trying to ingest a new language. It also facilitates interesting learning exercises. I think these types of exercises that make you create in a new language anticipate the problems you will face as a missionary answering contacts' questions in a foreign tongue. They also fight classroom boredom.

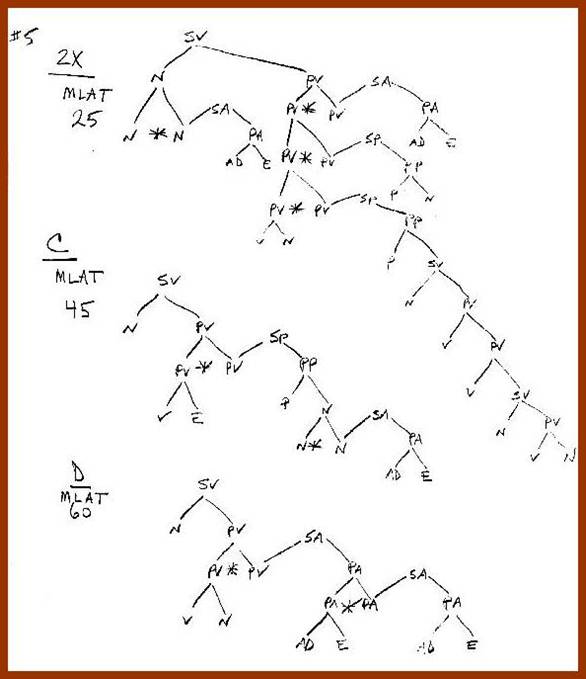

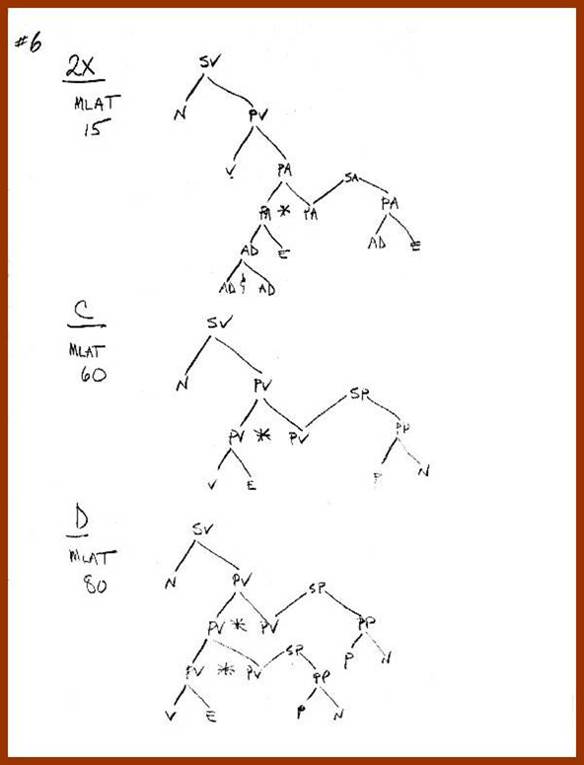

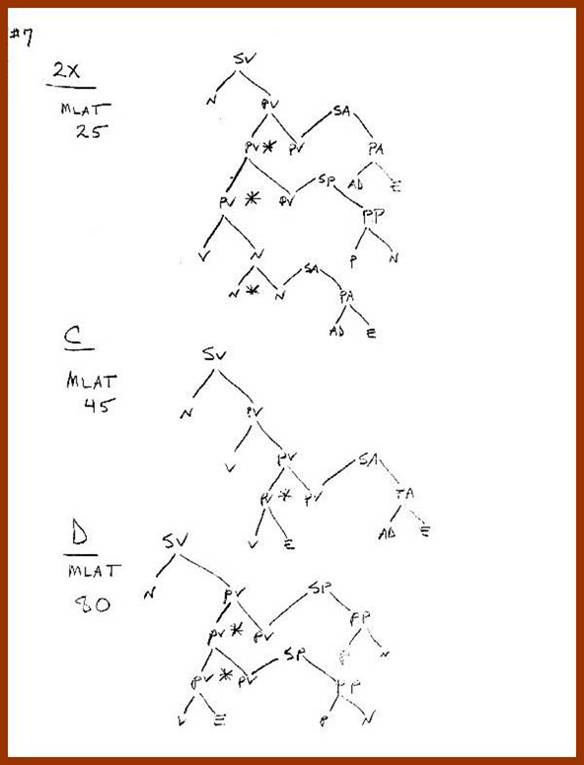

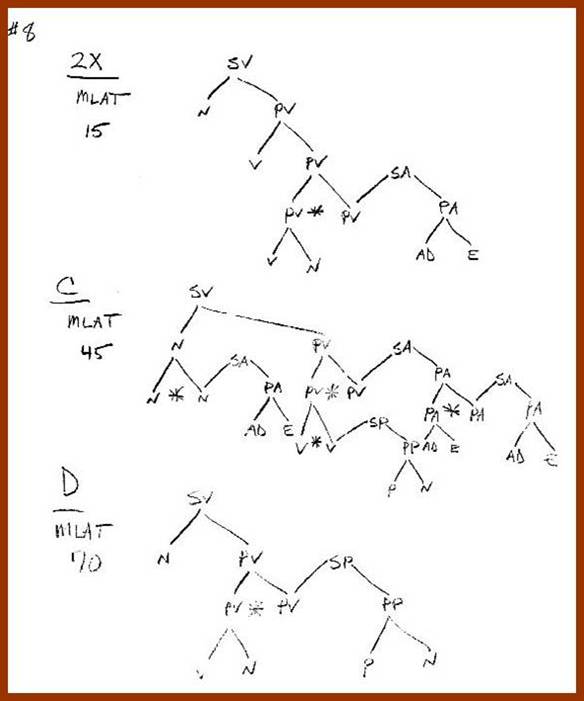

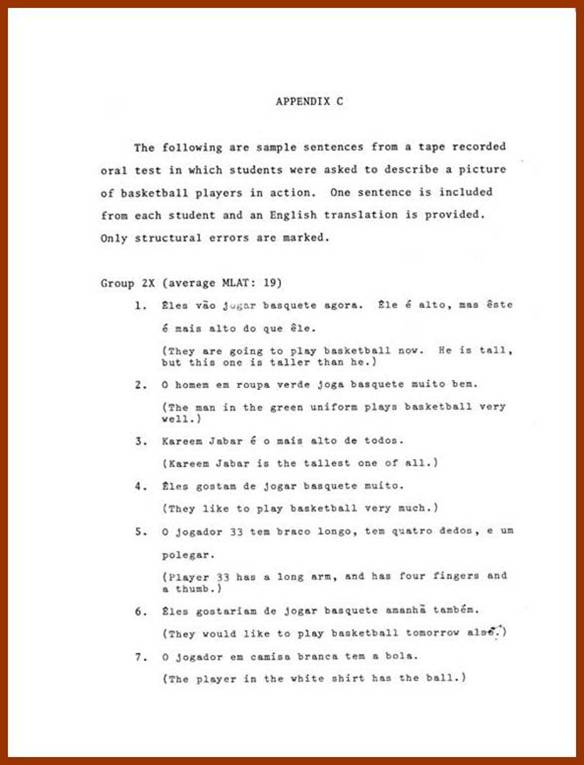

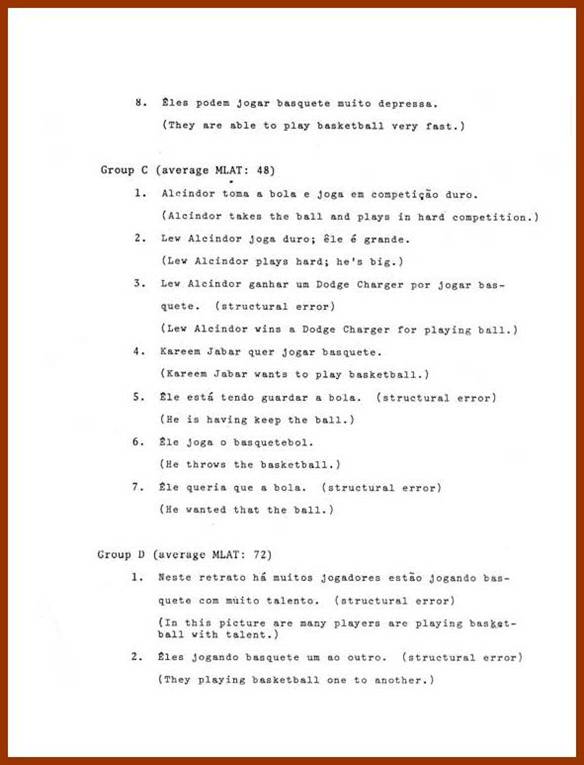

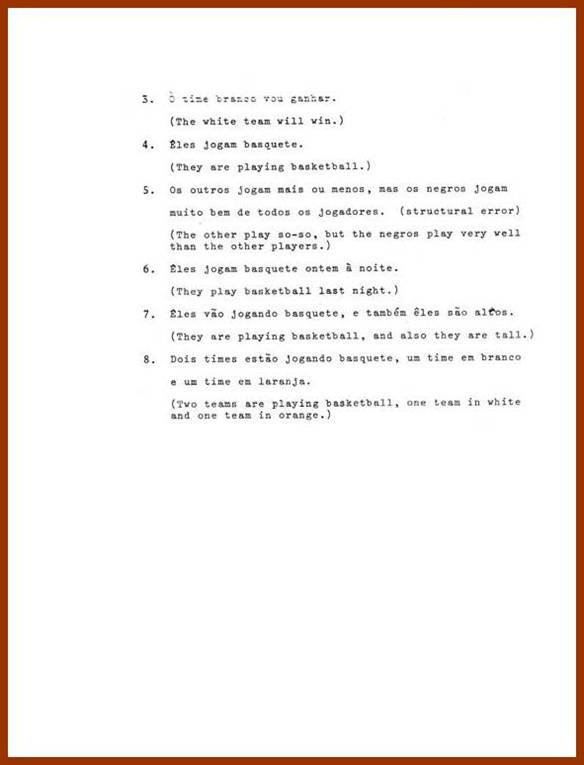

Because of the favorable results of this first experiment, a similar experiment was conducted following the same format as the first. In the second attempt, however, the test group consisted of eight low profile language learners with a group average MLAT of 19. (This group will be referred to as 2X.) Concurrent with the second experimental group were two groups (C and D) with average MLAT'5 of 48 and 72, respectively. Groups C and D did not learn junction grammar.

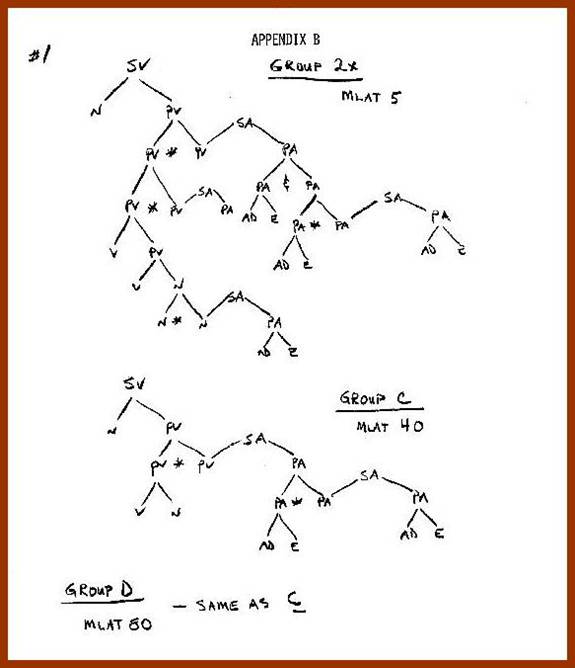

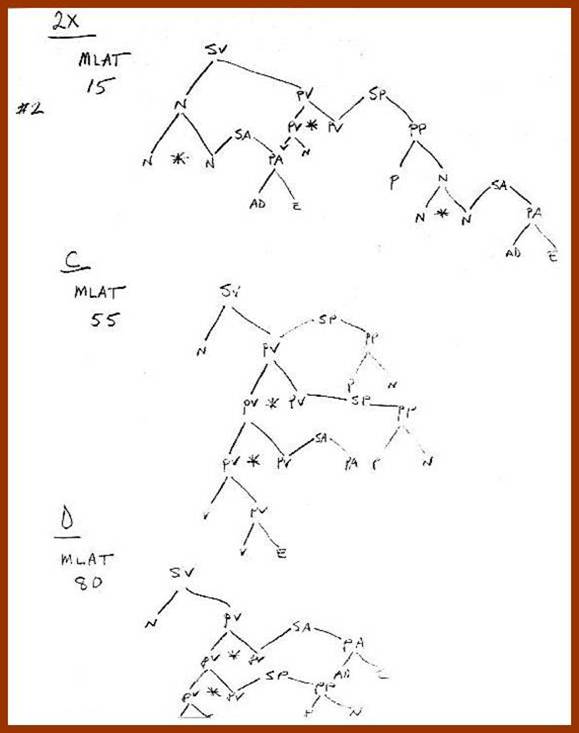

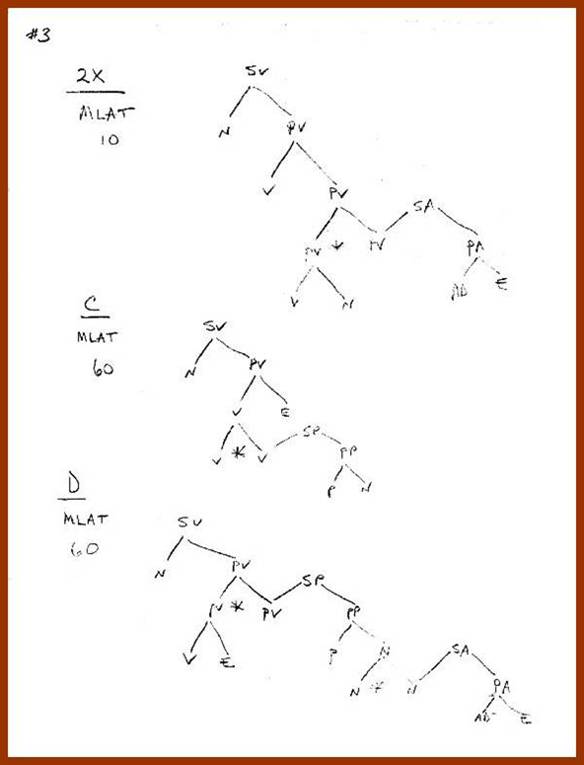

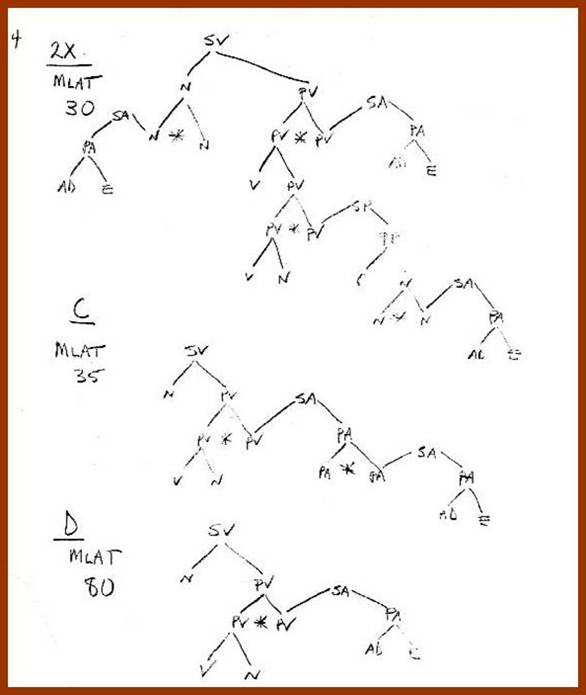

The results of a major creativity test which was given to all three groups are presented in diagram form in Appendix B. In this test, students were asked to write sentences from lists of parts of speech. The series of diagrams in Appendix B compares these sentences in groups of three. The most complex sentence from each student in each of the control groups is included.

In this test, group 2X had no unacceptable structures, two categorial errors, and eight agreement errors. Group C had one structural error, no categorial errors, and two agreement errors. Group D also had one structural error, no categorial errors, and four agreement errors.

These results were typical of the overall performance of the three groups. Although group 2X usually committed more grammar errors, they consistently used structures whose complexity was equal to or greater than those of the other two groups.

Group 2X's tendency to make fewer structural errors than the other two groups and to use structures of comparable complexity was also evident in oral tape-recorded tests in which students were asked to talk about given pictures in their target language. (See Appendix C.)

Based on the results of these tests and classroom experience, it is my opinion that in the area of free conversation, group 2X has performed better than previous groups of similarly low aptitude. At the same time, their performance in comparison with the two higher aptitude groups does not reflect as great a disparity as the average MLAT scores would indicate.

We feel that the positive reaction of both students and teachers to the system, the encouraging initial test results, and the apparent facility with which the test groups handled the structures of the language in a conversational context, divorced from script-like memorized material, warrant further development, experimentation, and testing in order to design an approach to language learning which provides a clear, diagrammatic perception of language structure. We feel also that this tree diagram approach offers a basis for more systematic organization of the sequence in which study materials are presented. Hopefully, the new approach will better enable students to construct sentences in creative, conversational contexts.

|